An argument that I hear too often from various progressive reformers and those, like abolitionists, to their left is something along the lines of “police do not reduce crime.” It’s a frustrating argument to hear, because it is simply empirically untrue. Police do reduce crime, with perhaps the best study I’ve seen recently arguing that every 10 additional police officers prevent one murder and ~20 serious felonies.1 Arguing that police are completely ineffective thus forces reformers to defend a position that is empirically untenable.

Which is bad in and of itself, but perhaps even worse because it distracts us from a much more empirically compelling challenge to our current levels of policing: not that policing has no effect on crime, but that the opportunity cost of policing is too damn high.

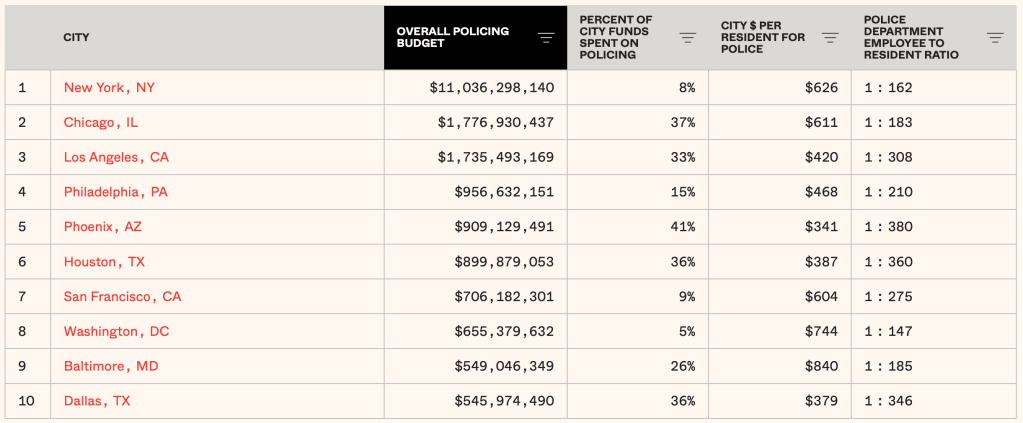

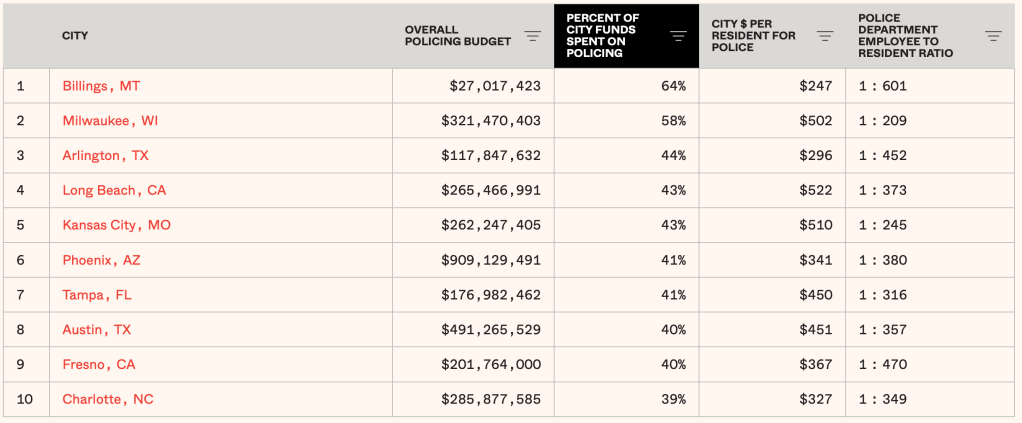

Policing often takes up a significant chunk of local budgets, which means spending more on policing likely means spending less on something else. A study by the Vera Institute for Justice of big-city budgets in 2020, for example, found that in many places the police department consumes something on the order of 25% to 30% of local budgets.2 Here is policing’s share of local budgets for the cities with the ten largest departments in the Vera dataset:

And here are the ten cities with the biggest share given to policing. Ignoring Billings, MT (which has a population of only 117,000 people), these are all respectable-sized cities, and nearly half of their spending is tied up in policing.

So even if policing works, the question is does it work well enough to justify the share of the budget it has?

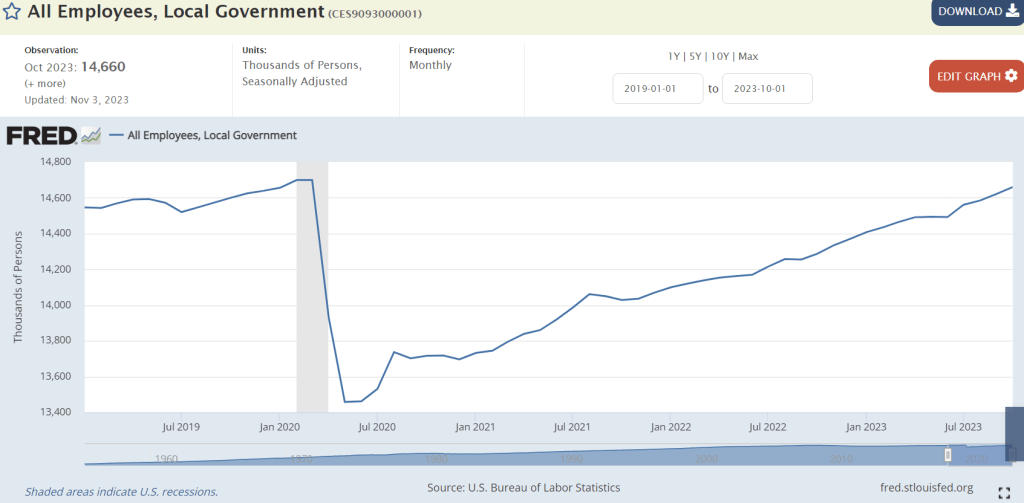

Which brings me to an excellent recent Substack post by John Roman, the director of the Center on Public Safety and Justice at NORC. In trying to explain the causes of the 2020 homicide spike, Roman zeroes in on a Covid-related shock that has gotten too little attention: a precipitous decline in local government employment. As he points out, that employment declined by about 10% during the pandemic. This graph, which I have lifted from his post, shows the decline pretty clearly.

Roman’s argument, is that this decline contributed to a significant reduction in all the various non-police services that we know help reduce and contain violence. And that in turn was a major–and majorly overlooked–driver of the homicide and shooting spike of 2020 (one, Roman argues, and I agree, that is almost surely more significant than any alleged “Ferguson/de-policing” response to the George Floyd protests).

It’s a compelling argument, because there is ample evidence that all sorts of non-policing options work to reduce crime. A 2020 study by John Jay’s Research and Evaluation Center, for example, lists dozens of alternatives, ranging from improving the physical environment to drug treatment to youth support to financial assistance, all of which had demonstrated success in curtailing violence. Other research has found that expanding drug treatment, including via Medicaid Expansion, appears to produce noticeable declines in crime. In some cases–although the comparisons here can be tricky–these programs appear to be more effective in reducing crime, dollar-for-dollar, than investing in policing.3 And even if their crime-reducing impacts are overstated, the social costs of these programs are lower (drug counsellors rarely shoot dogs or injure babies with flash-bang grenades), and these programs provide valuable social gains beyond crime reduction (like getting someone to quit using drugs in harmful ways).

But all these programs need (non-police) local government employees to function, and funding from the budget. Yet in all of our debates about crime and crime reduction, we talk far too little–basically never at all–about the need to make sure these programs are adequately staffed and funded as well. Nor do we ever really ask where the money for more police has to come from, what programs get less so the police can get more; police funding usually seems to be treated as if it comes with no tradeoffs, which is … not the case.

As Roman laments at the end of his piece:

“In closing, let me just say that there are about 55,000 coal miners in America, and we seem to talk about them all the time. There are something like 700,000 local government employees who wear a badge, and much of the political discourse revolves around whether that is the right number. There are more than 13 million other local government employees and we never hear a peep about them.”

https://johnkroman.substack.com/p/why-violence-spiked-in-2020-in-one

There’s at least one more empirical reason why we should pay a lot more attention to these sorts of programs and how they are staffed: because contrary to the conventional wisdom, these programs, not policing, are most likely the true first responders to crime. While it is true that police do reduce crime, it is still important to note how much crime they do not interact with. Here are the two big filters.

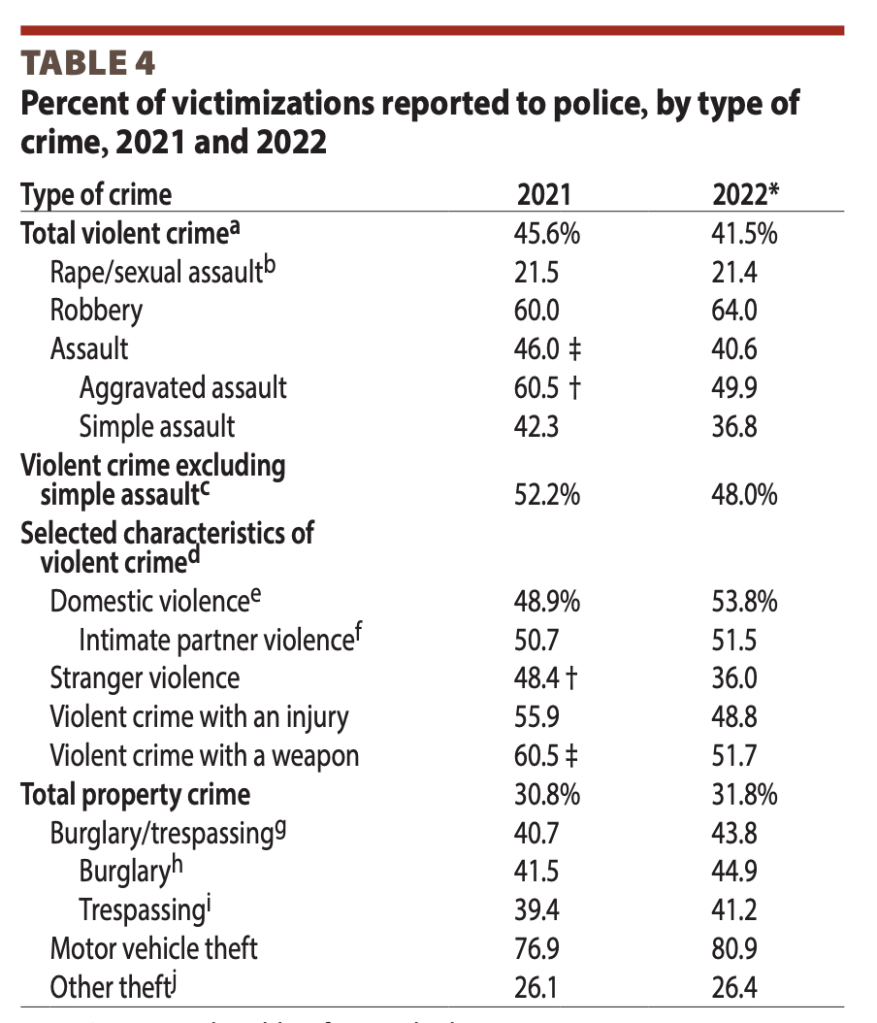

First, for most types of crimes, people are more likely to not report than to report. Here are the most recent numbers, from September’s release of the 2022 National Crime Victimization Survey:

People report just about half of all crimes of violence (and only 1 in 5 rapes), and for property crimes it’s only car theft (for obvious reasons) that gets reported with any real regularity regularly.

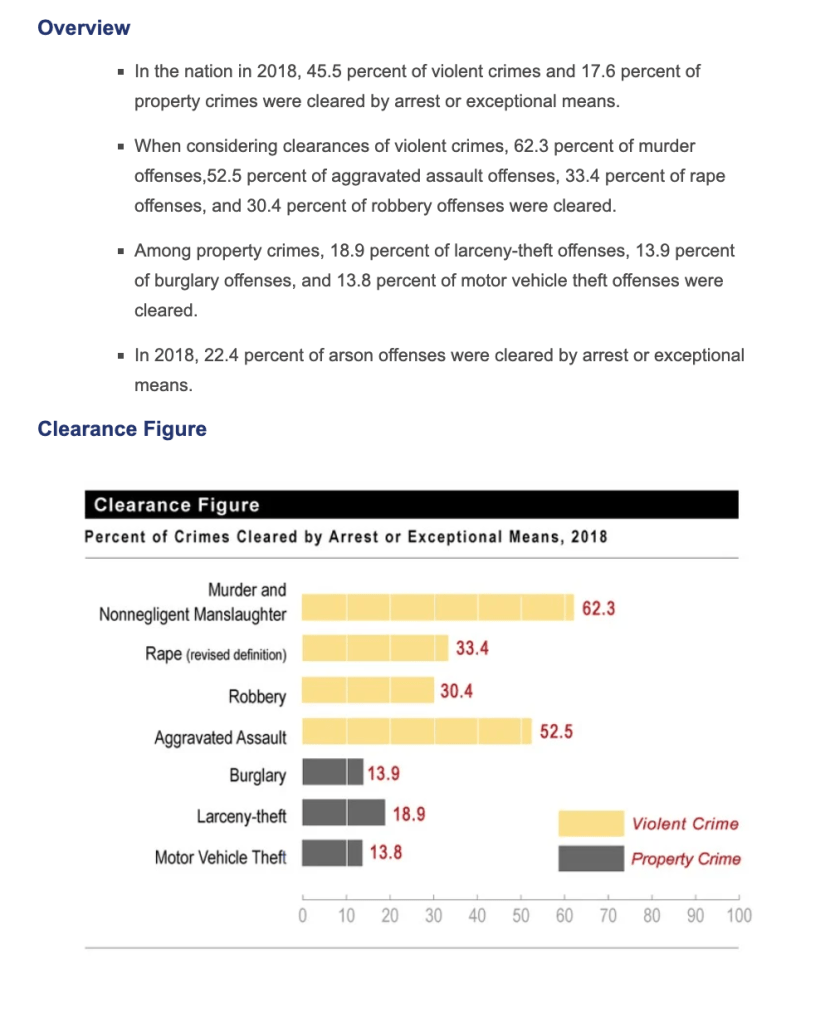

Even if a crime gets reported, however, that doesn’t mean there will be an arrest. Here are the clearance rates–the percent of crimes known to the police that result in an arrest–from the 2018 Uniform Crime Reports:4

So think about what this means for, say, aggravated assault, a crime with both high reporting rates and high clearance rates. If only 49.9% of those assaults get reported to the police, and they make arrests in only 52.5% of the cases, that comes to ~26% of cases resulting in an arrest.5 And that’s for one of the most reported and most arrested offenses. For theft, an 18.9% clearance rate for a crime reported only 26.4% of the time means that ~5% of thefts lead to an arrest.

Which suggests that whatever effect police have on crime–and it is clearly a non-zero effect–it’s likely that other institutions that interact with at-risk people on a much more regular and consistent basis are having far bigger impacts on those people’s behavior. And, again: those institutions can’t function without people. People whose importance we seem to consistently undersell.

.

- The study also found that those ten additional officer lead to ~70 more low-level arrests and cause ~8 more excessive-force complaints. This is one reason why I think it’s one of the best papers on policing and crime: because it is one of the few to consider not just the fiscal but the social costs of crime when running a cost-benefit analysis of policing. ↩︎

- Intercity comparisons require a certain amount of caution, if only given the complexity introduced by differences in intergovernmental transfers from state governments. My understanding, for example, is that in some places the state government injects money for K-12 education into the local budget that can only be spent on the schools, while in others the state spends that money directly; those injections increase the local budget, and thus reduce the percent spent on policing, but they are not funds that the city has much control over. ↩︎

- If nothing else, in many of these cases the evidence comes from pilot programs, and there is often a concern that returns can decline as programs scale up. ↩︎

- The 2019 results are roughly the same; I chose 2018 because it has the picture, which for some reason has been broken on the 2019 version for years now. Why stop at 2019? Because by 2020, we basically stopped having national crime data, and we still don’t have it back yet. And note that there is a lot of small print when it comes to computing clearance rates (like an arrest in 2019 for a crime in 2017 counts towards the 2019 clearance rate, and “known to the police” is a … complicated term). ↩︎

- To be clear, the idea that we know clearance rates to the tenth of a percent is preposterous, given the errors and crude interpolations run through the UCR. And the fact that the FBI has almost never reported error bars, while giving highly-precise count (thefts down to the one’s place!), has always struck me as deceptive hubris. ↩︎

Pingback: How to Successfully Get Out of an Aggravated Assault Charge - Writ of Habeas Corpus