For a while now, I’ve been seriously concerned about the threat that state-level preemption poses to local criminal legal reform efforts. But as I’ve dug into it more, my views have become … confused. I don’t think it is irrelevant, and it may still pose a dire threat to reforms. But also? Republican efforts to use it fail far, far more often than they succeed. But our empirical understand here is really pretty thin, and in this post I want to share some preliminary data I’ve gathered on these sorts of state efforts.

It probably helps, though, to define the issue first. “Preemption” is one of those dry legalistic concepts which, because of its dryness, often flies below the pop-culture radar, potentially allowing it to do tremendous harm out of the public’s eye. Oversimplifying a bit, the idea behind preemption is pretty straight-forward: as a general matter, state legislatures are free to impose whatever rules they would like on their cities and counties, or to reverse, undo, or restrict any local laws those places want to adopt. This is the doctrine which, for example, allowed conservative states to ban local mask requirements during Covid.

Now, of course, the reality is a bit more complicated than that. Some states have various sorts of “home rule” laws which gives cities and counties some protection from state interventions; those sorts of protections have actually already forced the Florida legislature to roll back an aggressive criminal legal preemption bill, and may yet undo a Texas preemption law so expansive it was nicknamed “The Death Star.”

But these protections tend to be weak, and experts have been warning for a while now that a wave a “new preemption” posed an existential threat to all sorts of local self-governance. Governing Magazine, by no means a tabloid, went so far as to run an article with the title “States Preempt Cities Almost to the Point of Irrelevance.”

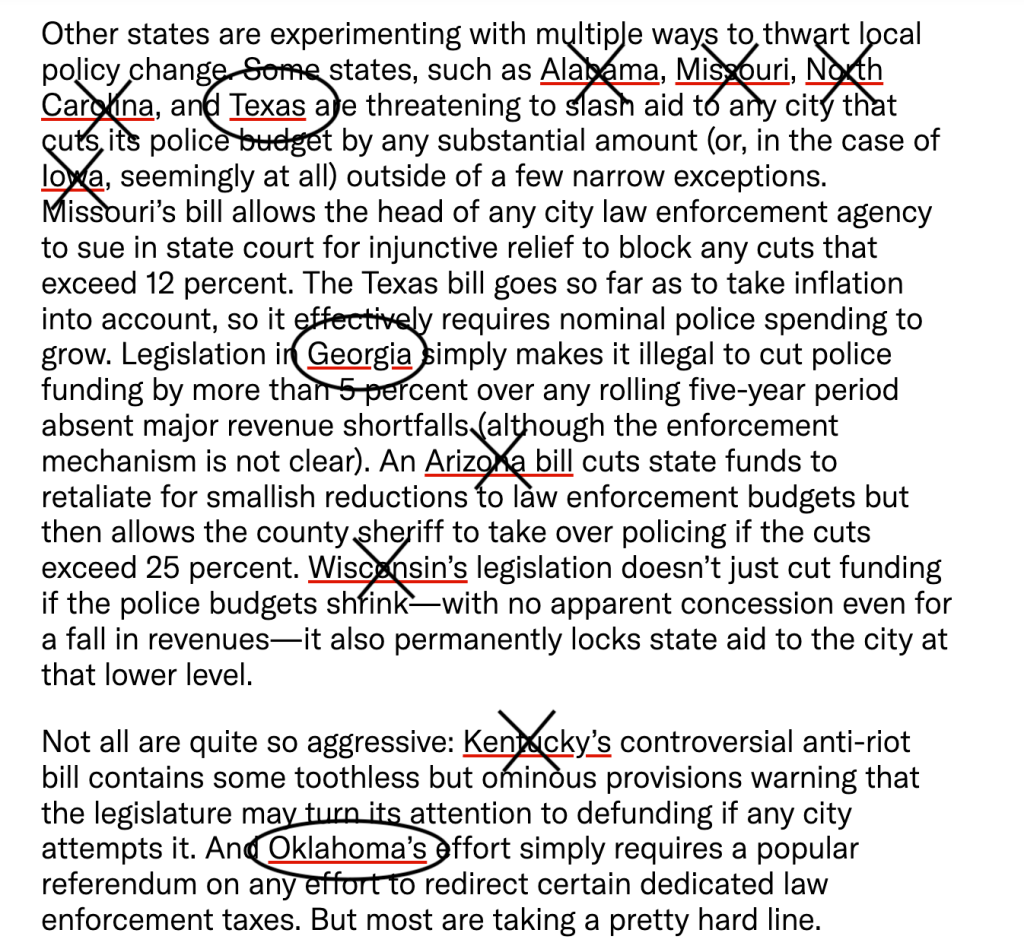

I first started focusing on the threat preemption posed to criminal legal reform back in 2021, when I wrote about thirteen bills introduced in state legislatures in nearly a dozen Republican-leaning states, such as Texas, Florida, and North Carolina, aimed at thwarting local efforts to just cut (not even “defund”) policing budgets. In that piece, I pointed to Florida’s just-passed HB1, which gave the governor almost unfettered power to restore any budget cuts to local police departments, and then highlighted ten other states that were “experimenting” with ways to limit local control over police budgets.

In that piece, I noted that three of those thirteen were earlier efforts that had failed, but to me those were the exceptions, not the rule. “The passage of HB1 in Florida suggests, however,” I wrote with great confidence, “that the current crop of anti-defund bills have better chances of succeeding.”

Not so.

This past year, I decided to go back and check the fate of the anti-defund bills I had written about a few years before. Of the thirteen bills, only four passed (or just four of the remaining ten) the legislatures. And one of those, passed in Wisconsin, would fail to survive a gubernatorial veto, despite overwhelming GOP majorities in both chambers.1

Suddenly, these preemption threats didn’t seem so aggressive. Lots were introduced, and lots failed. Because that’s the nature of all state legislation: lots are introduced, lots fail. One study estimates that only about 20% of state bills make it into law; three out of ten to thirteen is just right around that.

So I decided I wanted to dig into this issue a bit more deeply. This summer I had some research assistants go through all state bills introduced since ~2020 (when Covid + the George Floyd protests really seemed to animate the GOP backlash against reform efforts) in several conservative-dominated states with liberal-leaning cities that have been political battle-grounds on criminal legal reform. The project is still underway, but here I will post the Google Sheet with my preliminary results from Texas, Florida, Indiana, Ohio, and Missouri. I still have data from South Carolina to work through, and I still have more states to gather, such as Arizona, North Carolina, Tennessee, and others.

Besides making these results public–and issuing a crowd-sourcing request to please, please, PLEASE pass along any bills you think I may have missed here–I want to touch on two issues that have come to my mind as I’ve worked my way through all these laws. First: how should we count “success rates” here? Second: what does it mean for a bill to “succeed”?

But first, here are the results.2 Green are bills that get signed into law, red are ones that die, and gray are bills that … die, but die because (at least in Texas) different legislators will often introduce their own versions of the same bill, only one of which can survive. So the specific bill dies, but its idea survives. Pending bills are unshaded.

Ok, now on to the points that intrigue me.

What is the Success Rate?

At one level, it seems like the overall “success rate” should be just the ratio of bills passed to bills introduced. But just looking at the handful of states here reveals at least two problems with that.

First, at least in Texas, lots of “dead” bills are alternative versions of a final bill that the state legislature coalesces around. In 2023, for example, HB 17, which made it easier to remove an elected district attorney, got signed into law, but there were eight other bills that attempted to do almost the exact same thing, just ended up not winning the day.3 It seems somewhat unfair to argue that the passage rate here is ~11%; at the same time, putting it at 100% ignores that the alternatives may have differed somewhat, and may have still used up valuable legislative time.4

Second, I admire the extent to which Democrat representatives and senators in the Missouri legislature repeatedly introduced bills to regulate investigations into police shootings, ban chokeholds, and strengthen civilian oversight boards, but … man. The goal clearly was not to pass such laws, since the GOP has had supermajority power in both chambers for basically a decade now (and solid majorities in both since 2002). These bills have zero chance of passage; I don’t think the legislative App State ever upsets Michigan in these conditions.5 Obviously Democrats are introducing these bills for other reasons, such as forcing Republicans to speak out against banning choke holds, or to show their constituents that they are trying their best.

So I’m not sure we should count these defeats the same as, say, the repeated failure by Missouri Republicans to enact a Law Enforcement Bill of Rights (three of which die in the House, one in the Senate). The former seems to point to partisan imbalance, while the latter seems to point to some sort of deeper political challenge that these bills apparently face.

Finally, it is essential not to lose sight of the fact that the legislative process doesn’t stop with passage: these laws keep getting attacked. Sometimes successfully, even in surprising places. Florida’s HB 1, which inspired my 2021 article in The Appeal, was quickly attacked by numerous cities as violating the state’s Home Rule law. Last year, the state legislature amended HB 1 to scale back a lot of the governor’s powers after state courts refused to dismiss the case at summary judgment. So even one of the few laws that passed in my example didn’t survive unscathed.

In short, if we want to get a sense of the “success rate” of preemption efforts, I’m currently absolutely baffled as to what the correct metric should be. And it certainly seems like it is one that requires a fair amount of attention to the specific bills: one cannot simply looks at the number signed into law and the number introduced.

What Counts as Success?

In Missouri, every preemption bill I have so far identified going back to 2019 failed: an 0-for-60 run. Now, as I just pointed out, a bunch are efforts by Dems, but a majority are seemingly red-meat stuff for anti-reform Republicans, like giving the Attorney General more power over local cases (especially from unnamed big cities), allowing more chances to impose special prosecutors, expanding cities’ abilities to improve police political autonomy, etc.

Whatever story I want to tell next, that really is striking in and of itself, and I think tells us something about the politics of preemption. I flesh this out more in a paper I have coming out in the near future in the Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology (and which isn’t up on SSRN yet, but will be soon), but to me this suggests that perhaps being tough on crime is more of an electioneering device than anything else: that the politics of being tough are such that its a good thing to campaign on, but not something the party leaders are necessarily willing to expend much political capital on.6

But back to Missouri, because I chose that state for a reason. For years now, state Republicans have been targeting St. Louis’s reform DA, Kim Gardner.7 Many of the bills that failed were aimed at cutting back her power, if not outright removing her. In the end, however, she agreed to resign in exchange for the state legislature dropping its most-recent power-stripping bill (which other local prosecutors disliked as well). Officially, that bill and all its predecessor and alternates show up in my spreadsheet in red, as bills that died. But … they sort of did their job too. And perhaps their cumulative effect is part of the story (so it isn’t just the 2023 bill that “worked,” but all the harassment of its predecessors as well).

The shadow these laws cast thus cannot be ignored. Here’s another example, for example: Memphis DA candidate (and eventual DA) Steve Mulroy became very cagey about abortion prosecutions post-Dobbs in part to avoid the attention of Republican state legislators in Nashville. Bills don’t have to pass to send messages.

Any Sort of Takeaway?

On the one hand, these bills don’t seem to pass with any real regularity. That may seem to be an argument for more aggressive local reforms, and an unwillingness to be cowed by state-level threats.

But maybe they don’t pass that often because the threats work; maybe if local officials hold strong, state Republicans would feel compelled to pass more of these laws. And also, once a law passes, it remains on the books indefinitely–a low annual success rate combined with long-run attention would, in time, result in major cumulative rollbacks. But maybe that attention isn’t really there.

All of which is to say: the politics here are really puzzling, and–as is the case far too often with state, local, and state-vs-local politics–mostly unstudied empirically. This is just an early effort to start to try to gather the data needed to understand the politics of preemption, at least when it comes to criminal legal reform.

.

.

- For those who want to get into the weeds, here are the Legiscan links for all these bills: Alabama’s died 50% of the way (https://legiscan.com/AL/bill/HB445/2021), as did Kentucky’s (https://legiscan.com/KY/bill/SB211/2021). Missouri’s only made it 25% (https://legiscan.com/MO/bill/SB66/2021), as did North Carolina’s on police funding (https://legiscan.com/NC/bill/S100/2021) and on protecting its monuments (https://legiscan.com/NC/bill/H356/2019), Arizona’s (https://legiscan.com/AZ/bill/SB1333/2021), Pennsylvania’s monument protection bill (https://legiscan.com/PA/bill/SB1321/2019), Indiana’s (https://legiscan.com/IN/bill/SB0436/2020), and Iowa’s (https://legiscan.com/IA/bill/SSB1203/2021). The only ones to make it into law were Texas’s HB1900 (https://legiscan.com/TX/bill/HB1900/2021), Georgia’s HB 286 (https://legiscan.com/GA/bill/HB286/2021), and Oklahoma’s SB 825 (http://www.oklegislature.gov/BillInfo.aspx?Bill=SB825&Session=2100). Wisconsin’s Republican-dominated legislature managed to pass its version, but it could not override the governor’s veto (https://legiscan.com/WI/bill/SB119/2021). ↩︎

- Just to head off one potential valid criticism I’m already thinking about, I coded the legislative years by two-year terms (so 2023 and 2024 are both 2023), but realize that at least in some states, bills need to pass within a calendar year, so a bill may appear twice in a single legislative term, just in different calendar years. This is easy to fix–and to catch just looking at the file–because each Legiscan link includes the calendar year, even though my “Legislative Year” column is the first year of that legislative session. ↩︎

- It’s worth noting that while HB 17 definitely appears to be the favorite if we just look at sponsors, it wasn’t the only heavily-sponsored option. HB 17 had 65 sponsors, but one alternative, HB 1350, had 33; the rest had between 1 and 6, most just 1. That said, in other cases, the winner is the one with the most sponsors by a long-shot–but then, I don’t know enough yet about Texas legislative process to know if bills pick up sponsors as they gain steam. Does the sponsor count drive or merely reflect the likelihood of success? ↩︎

- Also, perhaps these defeated bills acted more like a type of amendment process, and so they shouldn’t count as separate bills at all, and perhaps in other states wouldn’t emerge as separate bills but as amendments? I get why people study Congress so much: one legislature with one set of rules. State and local government is where the law really is for so many parts of life, but it is also a total pain to study, given that there are a bajillion different rules to keep straight all the time. ↩︎

- As a lifelong U of M fan, this analogy is almost physically painful, were it not for the fact that the rehearsal dinner for our wedding was held at App State’s beautiful Turchin Center (with the added bonus that when we booked it, they warned us they couldn’t tell us what they’d be showing when we finally had our dinner, and some of my more conservative Catholic relatives were a little startled by the gorgeous-but-giant 30-foot high Maxfield Parrish-esque nudes that happened to be showing then). ↩︎

- The tl;dr here is that the economic benefits of being tough on crime (rural prison staffing, etc.) are pretty concentrated, even within the Republican caucus, so it may be hard to whip the votes needed to get something out of committee and onto the floor. Great to run on–everyone responds to fearmongering–but not enough fiscal winners willing to burn the political cash and effort. ↩︎

- The attacks were clearly politically motivated. But it was also the fact that the DA’s office during her tenure suffered from extreme staffing problems that few other DAs confronted. While most reformers lose staff, especially senior staff, when they come into office, Gardner often faced staffing shortages on the order of 50%, which is a massive–and destabilizing–shortfall. ↩︎