One project I’ve been hoping to start up on here (as I get back to posting after a slightly too-long hiatus) is a periodic series on some of our official criminal legal statistics and what they do and don’t mean. So I wanted to start with what I consider to be the single most challenging, difficult-to-use, regularly-misinterpreted statistic out there: recidivism. Which, unfortunately, is also one of the most important, since it is often one of the key go-to statistics for quickly saying whether things are “working” or not.

A quick clarifying point before I start. I’m using the term “official statistics” here intentionally, and I’m referring to the numbers that government agencies generally report: FBI data on crime and arrests, Bureau of Justice Statistics on recidivism or offenses of those in prison, etc. There are lots of other sources for measuring these things, some in one-off research projects, others in more comprehensive longitudinal datasets, and so on. But I think the official, regularly-produced official government statistics play a central role in shaping how we think about and discuss things like crime, recidivism, and incarceration, so it is critical to understand what they do and do not say–especially since their administrative nature often means they flatten and condense highly-complex processes to very simple numbers.

So, with that caveat, on to “recidivism.”

There are (at least) two core problems with how we officially measure recidivism, one perhaps more obvious than the other. The more obvious problem is that we cannot really measure reoffending, just new contacts with the criminal legal system. But that means that our measure of recidivism depends on all sorts of factors that may not correlate cleanly with reoffending. We can’t, for example, see reoffending without at least an arrest, an event which depends in part on where the police are and what they choose to do, which can lead to both undercounts (when arrests are not made) or overcounts (when the arrest is an incorrect one).

I’ll come back to this issue in moment, but first I want to focus on a much deeper, conceptual problem that flows from this based-on-criminal-legal-contact definition: what we measure is a narrow type of cessation, not the broader, more realistic process of desistance.

Recidivism as Cessation, not Desistance

Let me start this section with a simple example:

Consider three people recently released from prison, each of whom had committed one robbery per week before being arrested. Upon release, Bob really tries to get his life back on track but struggles, given the innumerable hurdles we put in front of people released from prison. So about once a month, Bob still finds himself robbing someone to cover expenses. After several months of this, he gets arrested during one of his attempted robberies.

Carl leaves prison unaffected one way or the other. He committed one robbery per week before getting locked up, and he picks up right where he left off and commits one per week when he gets out. Unsurprisingly, he too gets rearrested relatively quickly.

Finally, Daniel is traumatized by his time in prison, and he comes out more violent than before. He continues to rob people, but now even more often than he did earlier. Like the other two, he also eventually get arrested during a robbery.

In our official statistics, all three are men who went to prison, were released, and reoffended. All three “recidivated.” All three “recidivated” in the exact same way. All three are indistinguishable in our data.1 Yet all three had very different, policy-relevant outcomes.

Put differently, our primary measure of recidivism defines “success” as cessation (a complete end),2 not desistance (a gradual, and perhaps imperfect, decline). Improving one’s behavior doesn’t count: either one never shows up again in the data, or one is a recidivist. Full stop.

Now, to be clear, criminologists have accepted for decades now that this is not the right way to think about complicated and often messy transitions people experience moving into and out of criminal behavior, and they have expended a lot of effort thinking about how to define and measure a more nuanced definition of recidivism and desistance that should distinguish Bob from Carl from Daniel. But as this overview by Michael Rocque makes clear, these studies of desistance do not use official admin data, but have to instead things like surveys. Rocque in fact notes that the one effort by the BJS to measure desistance using official government data effectively measured cessation, since its metric (shown below) is simply “never rearrested.”

In short, our official metric relies on an unrealistic view of behavior, which risk both understating successes (when there are more Bobs than Daniels) and failures (when there are more Daniels than Bobs).

The Difficulty of Measuring Even Cessation

The second problem is that even if we are okay with a cessation-focused definition of recidivism, official data struggles to measure even that, for several important reasons.

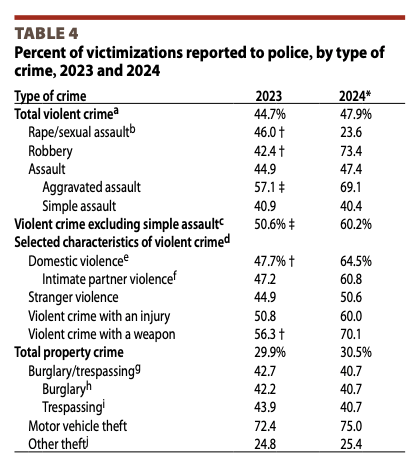

First, official data cannot measure what it never learns, and we know that a large percent of crimes are never reported: in over half of violent crimes and ~70% of property crimes victims never reach out to the police. Regardless of whichever official statistic one wants to count as a “recidivating” event–arrests, charges, convictions, incarcerations–we can’t count any of them if no one calls in the crime itself (unless the police happen to see it themselves).

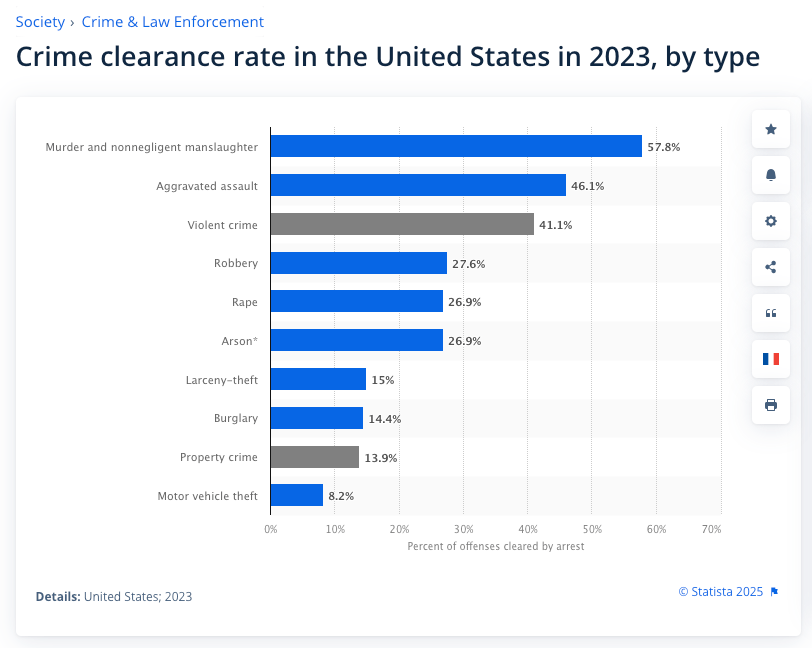

More limitations quickly follow. Even crimes that get reported cannot turn into a recidivating event absent an arrest,3 and our clearance rates there are low too.4 Overall, only about one third of crimes result in an arrest, and only homicide breaks 50% (and barely at that).5

All this suggests that official arrest data will underestimate recidivism rates, and thus any other metric (charges, convictions, etc.) will as well. Or at least may understate them. There’s actually a silver lining to defining “recidivism” as a failure to cease. We may not catch each, or even most, of the times Bob or Daniel commits a post-release robbery. But as long as we catch one of them, we still correctly determine that neither Bob nor Daniel ceased. It’s only the people who are never caught reoffending who we miscount in a cessation-based metric. Who, probabilistically, will be the ones who reoffend the least.

But putting that silver lining aside for a moment, there are two big implications that flow from the limitations in arrest numbers. The first is that we may be underestimating recidivism-as-non-cessation rates, even if not by as much as it may initially seem (because of the we’ll-arrest-them-at-some-point issue). The second, though, may be both less obvious and more significant. It’s not just that our measure is imperfect, it’s that that imperfection varies across groups. In other words, we are more likely to detect recidivism where we have more police to make the arrests, and the police are disproportionately in Black neighborhoods, even when we control for crime rates.6 Which means that our recidivism rates will have a racial bias to them that reflect the disparities in the mechanisms that produce the admin data in the first place. And those data-gathering-method-driven disparities are then used to justify the disproportionate policing that helped create them, in a vicious cycle.

And the challenges keep coming. Even when we have the arrest, for example, it’s worth asking when it should really count as “recidivism.” If Bob gets rearrested on a misdemeanor marijuana charge in a state that still criminalizes personal use while Carl gets rearrested for another armed robbery, both are “rearrested” and thus “recidivists,” but it seems problematic to treat them the same…

… except we also know that the somewhat-random nature of arrests means that the thing a person gets arrested for may not reflect the sorts of criminal acts they are generally committing. In other words, just because Bob gets busted for weed does not mean that that is all he is doing. It could be the cops missed his robbery the night before but happen to get him for the weed the following day, or maybe they arrest him for the weed rather than letting him go with a warning because they (here, correctly) suspect he’s committed some robberies. In other words, maybe we don’t want to treat Bob’s and Carl’s rearrests the same, but maybe we should if we think the current arrest is a weak proxy for what is really happening more broadly.7

But still: there’s a very real normative question of “what behavior should be seen as serious enough to count as `recidivism?’,” which is not trivial to answer in general, and is made all the more complicated by the extent to which our criminal code criminalizes all sorts of really minor behavior (in Georgia, every traffic violation is a misdemeanor). Then once we pin down that definition–which often is not done–there’s the challenge if figuring out if our data really measures those reoffenses correctly.

Also, note that I haven’t addressed the fact that while lots of crimes don’t result in an arrest, sometimes non-criminal behavior does result in an arrest, or the arrest is substantially overstated and later knocked down or dropped by the DA (so even trying to limit our definition of “recidivism” to felony arrests may not fully screen out what are in actuality arrests for low-level stuff that is initially over-charged by the police). Which again can throw off the accuracy of our metric … although our misplaced emphasis on cessation may at least partially save us here again.8

Using charging, conviction, or incarceration rates as measures of “recidivism” create even more problems … but also may provide some solutions. At one level, relying on prosecutorial screening may give us a better sense of the rate of more-serious reoffending, if we think that the ~25% of cases that DA offices appear to drop or divert skew towards the less serious. On the other hand, plea bargaining messes with our sense of what really happened–felonies can drop down to misdemeanors and violent crimes to non-violent ones not because of the actual events or the evidence but as part of the deal to keep the caseloads moving. More noise and confusion about what we are really measuring or tracking. Ditto using incarceration, which likely filters even more for severity (amidst some offsetting arbitrary parole enforcement decisions), but may even risk over-filter for it, given the relatively low rates of admissions to prison even for convictions for violence.

Conclusion

Ok, that’s a lot, so I’ll stop here. But hopefully the two main points are clear: (1) we are likely not measuring the right thing, and (2) our measurement of even the wrong thing is a messy. An extension of that is that our messy measurement of cessation likely can tell us very little about desistance. And that’s before we get to the issue of what crimes should count as “recidivating” events in the first place, and the limitations in our admin data in tracking those correctly (and whether, say, someone who used to regularly commit armed robbery shifting into less-frequent burglaries counts as a “success” or “failure”).

The metric we have is crude and blunt, and it’s essential to understand its significant limitations.

.

- Conceivably, if Bob takes three years to get rearrested, Carl two, and Daniel one, they would show up differently in years-to-rearrest. But that would be the only way to distinguish them; if two of them got arrested within roughly the same time after release, they’d be indistinguishable. ↩︎

- Well… a complete end to getting caught in the window in which we observe whether you get caught again. ↩︎

- Even if we wanted to use “reported to police” as the measure of recidivism, there’s no way to link the called-in event to the person who (allegedly) did it absent an arrest, unless the victim provides the specific name of the person. Even putting aside the reliability of such a claim, our data simply cannot link names in 911 calls to release data. ↩︎

- What counts as a crime “cleared” by an arrest is a tricky statistic in and of itself and will definitely be the subject of a future post. ↩︎

- I always prefer to use official data over something like Statista, but the FBI has made its crime and policing data distinctly hard to use. I checked the numbers against what is available on the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer website, and they tracked the Statista ones closely (which is good, since that’s the source Statista cites for the data here). ↩︎

- I suppose this is partially offset if it’s true that Blacks are less likely to call the police in the first place. ↩︎

- But figuring out that issue–what is the real set of behavior lurking under the one event that triggers the arrest–is really hard. ↩︎

- The problem is bigger here, though. Stochastic arrests mean that we have a higher chance of eventually catching the higher reoffenders for something at some point. But it doesn’t mean we will necessarily get them for the thing that best reflects the sorts of actions they are generally engaging in. If arrests are truly random–and they are not–I suppose on average we’d get people for their most common type of reoffense, but I think it is still pretty messy. ↩︎

Additionally, I suspect that police, given a list of suspects, are more likely to arrest someone “with a record”.

LikeLike