Every time there is a mass shooting event, opponents of gun control open with “thoughts and prayers,” and then quickly move on to mental illness, not the guns, being the issue. And it is true that many mass shooters suffer from mental illness; that is unambiguously the case with the recent mass murder in Maine. But there are two really big statistical flaws with this claim, one empirical and one conceptual.

Empirically, while mental illness may be a risk factor for violence (although evidence suggests it is more mental illness interacting with, say, bad environmental factors), it appears to be an even bigger predictor of victimization. And I fear our knee-jerk response to blame every appalling act of violence on “mental illness” only puts an already-vulnerable population at greater risk of further violence, by making a public that often views the mentally ill with disdain now view them with instinctive, reactive fear as well.

But the issue I want to confront here is the methodological one: even if it is true that mental illness correlates with mass shooters–even if it correlates strongly (i.e., most mass shooters have some sort of mental illness1)–that does not mean it is a good, or even accurate, predictor of violence. Which may sound counter-intuitive, which is why I think so many accounts of mass shootings and mental illness fail to highlight the risk.

The problem is one called “selecting on the dependent variable” (which is also known as “survivorship bias,” which is … not a good term to use here). The basic idea is that we can’t understand what predicts being a mass shooter just by looking at the traits of mass shooters. (This is also why all books by CEOs that you can buy at airports should be viewed with unflinching suspicion, which I’ll come back to at the end.)

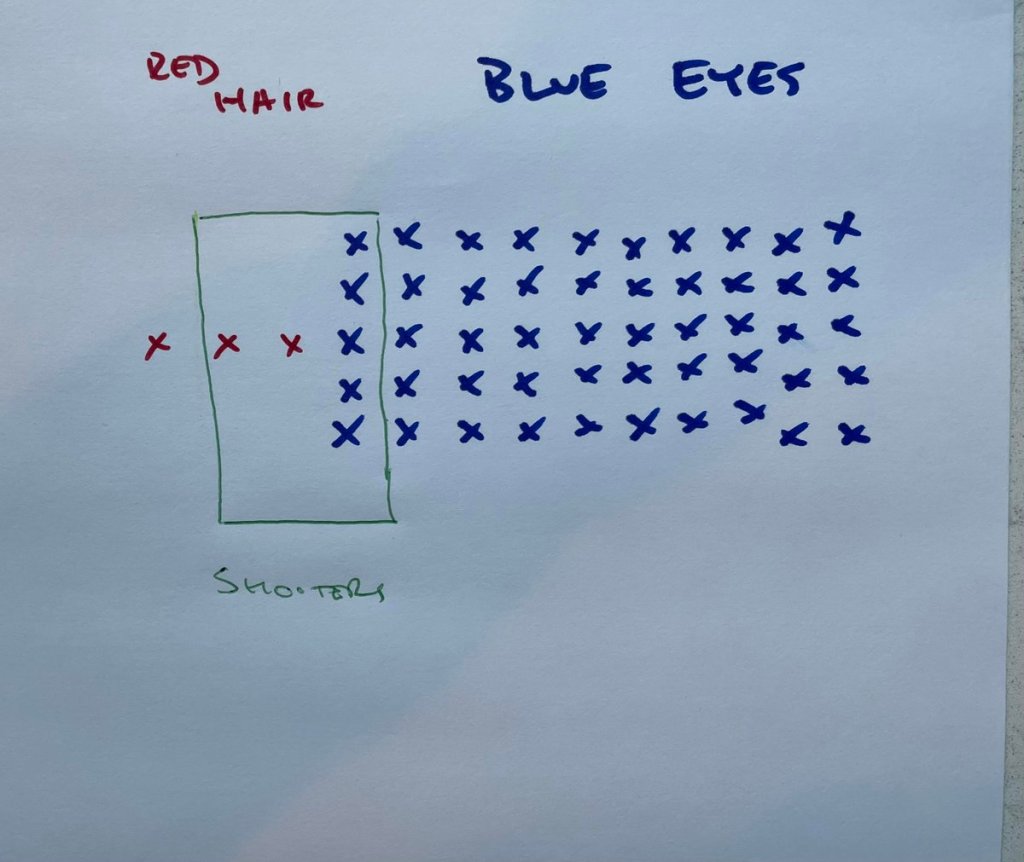

The picture below gives a simple example. Assume that we look at all our mass shooters, and we see that five have blue eyes, but only two have red hair.2 This might lead us to say that having blue eyes predicts mass shooters. After all, over 70% of all mass shooters have blue eyes!

But the picture also shows the problem with “selecting on the dependent variable,” where here the “dependent variable” (the thing we want to understand) is who commits a mass shooting. To know if blue eyes are a useful predictor, we can’t look at the population of shooters, we have to look at the population of blue-eyed people. Here, only 10% of all people with blue eyes commit a mass shooting, so intervening with all people with blue eyes would have huge false-positive error costs.

Now, that does not mean we should ignore blue eyes–they do have some predictive weight (maybe).3 But it does mean that looking at the shooter population doesn’t tell us what that predictive weight really is.

Conversely, under 30% of all shooters have red hair … but 67% of all people with red hair are shooters. It’s true that using red hair as the sole predictor means you’d miss a lot of shooters, but if you used red hair you’d at least stop a chunk with a high level of precision. And if you ignore red hair, you’ve introduced an avoidable false-negative cost. But, again: you cannot see that by looking at the population of shooters, only by looking at the red-haired population.

This problem likely plagues most if not all of our “predictors” of mass shootings–if only because the number of such shooters is vanishingly small (even if their terroristic impact is not), so any remotely-common trait will have little predictive impact. It’s surely the case for mental illness. It’s almost certainly true for a history of domestic violence, too. And on and on.

What we do with this problem, however, is not statistical but normative. For example, I am sure this problem exists when it comes to a history of DV, so banning gun ownership based on prior DV convictions will almost certainly deny guns to huge numbers of people who would not commit mass murder. Which is … fine by me. As a Second Amendment minimalist, the error costs of denying people guns is likely negative to me, so I’m cool with that. But someone with a more expansive sense of what the Second Amendment entails will end up someplace else.

As I mentioned up top, this problem bedevils everything. It’s why I hate airport bookstores, or at least the CEO “here’s how I succeeded” books that dominate the shelves. When I CEO writes that they did x and made a billion dollars doing it, we have no way to know if that was good planning, or they made a bad 1% bet, but they were the 1% that paid off. Because all the other CEOs who tried that and failed? They just disappear; no one asks them to write books. (This is why another term for this bias is “survivorship bias”: we just see the surviving firms, so we can’t see how often the policy didn’t work.)

This is actually why former MTV VJ David Holmes’ podcast Waiting for Impact was so amazing.4 Rather than interviewing the 90s-era boy bands that made it, he interviewed those that almost did but didn’t quite. And what you see is that they did almost everything the successful bands did, just the final coin toss came up tails, not heads. If you just talk to the winners, it sounds like “I did x, and x worked.” Talk to the losers, the ones we rarely see thanks to survivorship bias (and Holmes had to do a lot more digging to find his subjects), and you start to see how much less clear the link from x to success is.

Anyway, selecting on the dependent variable is a huge problem in how we cover what predicts behavior. And I think it is a big problem because it is so counter-intuitive and hard to see. A trait possessed by most mass shooters may not predict mass shooting? It may even predict not being a mass shooter? That’s … never immediately obvious, but it is always present.

.

- Of course, “mental illness” is such a broad term that the statement “most x suffer from a mental illness” is likely true for almost all, if not all, xs. Any discussion of “mental illness and x” really has to start by defining what sorts and degrees of illnesses they are talking about. But that’s a completely different rabbit hole to go down. ↩︎

- This example is not one of peculiar, quite-annoying-to-me “redheads have no soul” South-Parkian anti-redhead bias. I … might be surrounded every day by a horde of red-haired, blue-eyed children. ↩︎

- If 70% of shooters have blue eyes in a population that is 80% blue-eyed, then blue eyes actual predict not being a shooter, despite making up a majority of shooters. Background probabilities are really, really important. ↩︎

- It’s also why Guy Raz’s “How I Built This” podcast is so frustrating. ↩︎

Pingback: Reform Prosecutors: The Winners and the Losers – Prisons, Prosecutors, and the Politics of Punishment

Pingback: The Complicated Reality of the “Willie Horton” Effect – Prisons, Prosecutors, and the Politics of Punishment

What is really needed here is causality analysis and that is actually very hard, complicated, and usually there is not enough data.

LikeLike

Pingback: Reform Prosecutors Do Not Increase Crime: What the Data Tells Us – Prisons, Prosecutors, and the Politics of Punishment