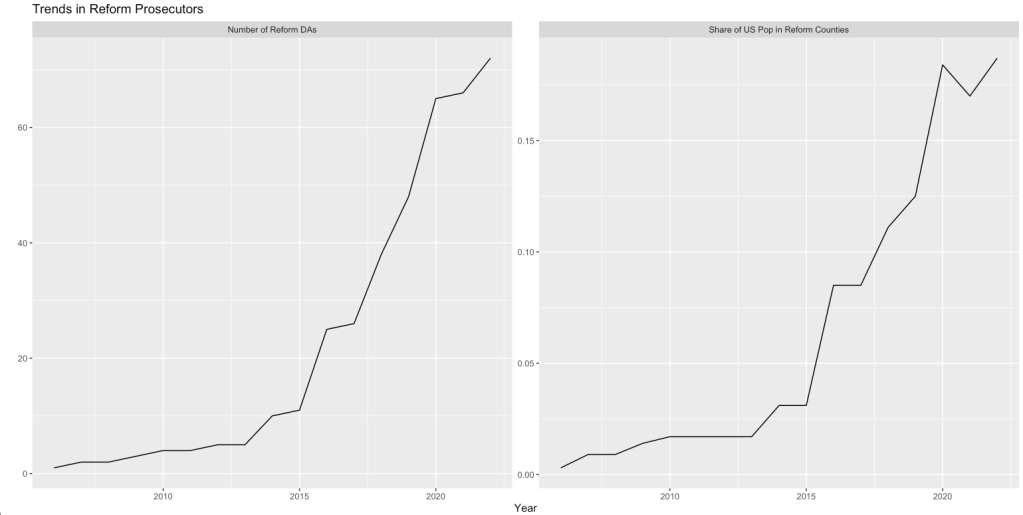

One of the more seismic shifts in the US criminal legal system has been the rise of the “progressive” or “reform” prosecutor.1 The first real high-profile reform victories were not even ten years ago, with Kim Foxx winning in Chicago in 2016, and Larry Krasner in Philadelphia in 2017.2,3 In those early days–just five or six years ago–only about 5% of the US population lived in counties with reformers.

Now? With over 70 or so reformers having won elections–in counties ranging from metropolises like Brooklyn, Manhattan, Cook County, and Los Angeles County to smaller places like Hays County, Texas, and Chatham County, Georgia–nearly 20% of all Americans live in counties where the prosecutor can be thought of as a reformer. In under a decade, “reform prosecutor” has gone from a concept that no one even talked about to one of the most significant flashpoints in the political struggle over criminal legal reform.

It really is one of the more remarkable recent developments in the politics of punishment.

To understand and model the drivers of this political movement, however, it is essential to put together a complete list not just of reform prosecutors, but of reform candidates–both those who have won and those who have lost. After all, to just look at the winners is to commit the statistical crime of selecting on the dependent variable. Moreover, almost all the discussions over reformers, pro and con, tend to focus on the same three or four people; even if those three or four serve in some of the biggest jurisdictions in the US, looking just at them gives an incomplete picture of what reform looks like right now, even if we are just thinking about those who have won.

Below is, I believe, the first such complete list. I developed this list back in January of 2023, and posted it back then to The Bad Place. It obviously needed a new home. I have not updated it since January 2023, mostly because not much has changed. But I plan to update it after each election cycle, the next of which is this November.

My main sources for this have been the always-outstanding lists of local elections at boltsmag.org; the list of reformers listed at the end of Prosecutorial Reform and Crime Rates by Amanda Agan, Jennifer Doleac, and Anna Harvey; and my own knowledge.

And I am always eager to hear suggestions, recommendations, and criticisms. The biggest challenge, of course, is deciding who makes the cut (I noted the problem with Kim Ogg above, and I’ve excluded the Bronx’s Darcel Clark, even though she has framed herself as a reformer). One future project I hope to undertake it to try to develop some sort of taxonomy of reformers by their reform-ness, so the list can be more nuanced than just the binary reformer-or-not, which homogenizes a quite heterogeneous population. Deciding what factors to consider and how to empirically separate rhetoric from action, however, are both daunting challenges.

In future posts, I’ll provide some of the basic patterns that have emerged from the data so far (several of which I’ve published here). But I want this post to just be about providing a fixed location for the raw data, so anyone who wants to use it has easy access to it.

.

- As I’m sure I’ll make clear in future posts, and have already written about over at Slate, I prefer the term “reform” to “progressive,” since the political base for reform prosecutors are not the quintessential “progressive” voters (who tend to be college-educated white people), but rather people of color, Black people in particular, often in higher-crime (and thus higher-enforcement) communities. ↩︎

- Defining who is a “reform prosecutor” is a tough, if not impossible, task, but by most definitions Foxx and Krasner were likely not the first, preceded at a minimum by John Chisholm (elected the DA of Milwaukee, WI, in 2007), Ken Thompson (elected the DA of Brooklyn, NY, in 2014), and Scott Colom (elected the DA of Mississippi’s 16th Judicial District in 2015). But controversies always abound; a Brooklyn public defender, for example, once told me that some people in his office thought Thompson’s predecessor, Joe Hynes, elected in 1990, was actually the more progressive of the two. ↩︎

- Some might notice that I didn’t list Kim Ogg of Houston here, who also won as a reformer in 2016. Her reformer status is … debatable. ↩︎

I understand that your list is not complete, but one omission I notice is the May 2022 election for DA of Washington County, Oregon (suburbs of Portland). Incumbent Kevin Barton defeated Brian Decker, who I think would fit comfortably as a “reform” prosecutor candidate by most reasonable definitions.

https://www.portlandmercury.com/news/2022/04/20/41004645/portland-is-the-boogeyman-in-washington-countys-da-race

https://www.wweek.com/news/courts/2021/09/13/public-defender-brian-decker-announces-bid-to-unseat-washington-county-district-attorney/

LikeLike

Pingback: Reform Prosecutors Do Not Increase Crime: What the Data Tells Us – Prisons, Prosecutors, and the Politics of Punishment