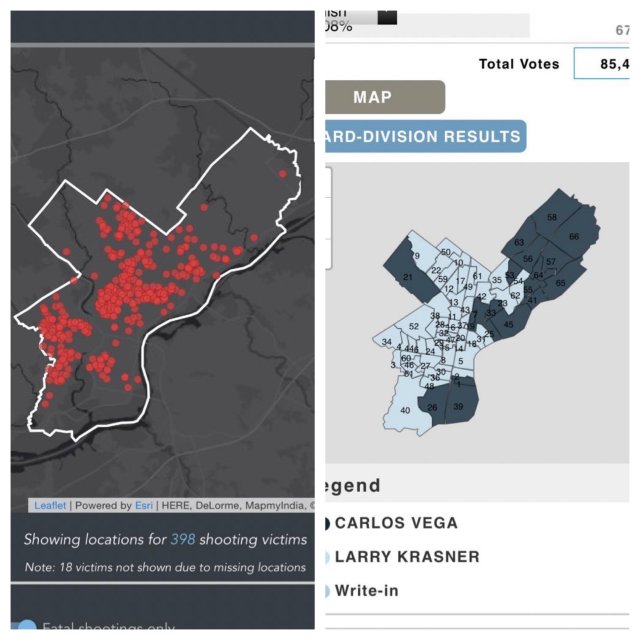

On the night of May 18, 2021, a racist tweet by an angry Philadelphian voter launched a whole new research agenda for me. As it became clear that evening that Larry Krasner had thoroughly defeated his Democratic primary challenger, Carlos Vega, a Vega supporter tweeted out the following pair of maps–of districts that went for Krasner alongside where shootings happen in Philly–with an angry “the definition of insanity” message.

All I could think when I saw this was: “so close.” The correlation was intriguing, and I was sure it not a spurious one. But it struck me not as the definition of insanity, but evidence that perhaps reform prosecutors’ biggest supporters were the most impacted communities.

At the time of Krasner’s re-election, it wasn’t clear that this was necessarily the case, in no small part because, as far as I can tell, there’s little empirical work in political science on precinct-level voting behavior for local races.1 So I decided to look, not just at Philly, but at a large number of cities and counties.

Over the next several weeks and months, I’m going to post my results–which, while primarily descriptive, I think represent the first real empirical evaluations of prosecutor races out there. I’ve already posted some results for Pittsburgh/Allegheny. Still to come will be places like San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles, both Baltimores (city and county), Queens, Manhattan, Dallas, Austin, Minneapolis, and several others.

In the meantime, here are some the broad patterns I’ve noticed so far.

1. The core support for reform DAs come from Black communities, at least up north.2 This is actually why I’ve stopped calling prosecutors like Krasner or Foxx (in Chicago) or Gonzalez (in Brooklyn) “progressive prosecutors” and started calling them “reform prosecutors.” Progressive as a political term refers to a partisan identification that is predominantly held by white people. The poor(er) Black residents of the communities that most support reform prosecutors may consistently vote Democratic, but their political views do not necessarily align easily with “progressive.”

2. “Communities of Color” likely obscures here more than it clarifies. I chose to say “Black communities,” not “communities of color” above, because that’s how the data seems to be playing out: support for reformers is weaker in Latino precincts than in Black ones. This seems consistent with the gaps that clearly exist between Black and Latino respondents to surveys about the criminal legal system. Latinos have less confidence than whites, but seem more supportive and trusting than Blacks. This likely isn’t just an issue when it comes to the criminal legal system–what we see here is an example of a broader convergence between Latino and white voters.

That’s not to say, though, that Latino communities do not support reformers. Especially in Texas, reformers have won in heavily-Latino counties like Travis (Austin), Dallas (um… Dallas), and Harris (Houston).3 But it’s not immediately clear to me that the politics will be the same in those places as in cities with large Black populations.

3. The suburbs. Even in very liberal counties–this will be clear when I show my results from Hennepin/Minneapolis, and this drove the results I recently posted about Allegheny/Pittsburgh–the suburbs tend to resist reform more than the cities. This appears to often be the case even in suburban precincts that are majority-Black or otherwise majority-non-white.4 They may still favor the reformer on net (though not always), but they consistently favor them less, even though they are less exposed to violence and enforcement. Those closest to violence are those who favor reformers the most. This is why it is not surprising that most reformers have been elected in counties where the county contains primarily (or only) the city itself. The bigger the suburban share of the electorate, the more reformers struggle.

4. Prosecutors and mayors are very different races. In 2021, journalists covering elections in NYC often seemed to frame things as “do voters want Adams (a former police officer) or Bragg (the reform DA candidate?” This is false dichotomy. Voters in higher-crime communities likely want both. They understand that the fastest way to target violence today is via policing, and the mayor controls the police. But they don’t want the sanction to be needlessly harsh, and that’s controlled by the prosecutor. Voters in higher-crime neighborhoods–unlike those in safer suburbs or parts of the cities removed from crime–have subtle, sophisticated views on how to respond to a social ill that directly impacts them.

I will assemble all of the county studies here.

.

- To be clear, I’ve looked and haven’t found any–and I’ve looked in the political science literature. Just want to be clear about that, since there may be some sort of history of economists saying “no one has done this thing yet,” when there are entire journals dedicated to that thing, just in other fields. If I am wrong about this–and I would definitely be happy to be wrong–please just let me know! I’m sure there’s little on DAs–their races were never competitive until a few years ago–but I haven’t been able to find much, if anything, on mayors either. ↩︎

- Obviously, nothing here is ironclad. In Queens a few years back, majority-Black precincts voted strongly for the less-reform minded candidate, while majority-Hispanic precincts generally went for the reformer. As I’ll discuss, this had a lot to do with the unique politics of Queens at the time (it’s sort of AOC’s fault, albeit indirectly). Local races are local. It’s clearly going to be the bane of any effort I make to draw generalizable conclusions with this project. ↩︎

- Is Harris’s Kim Ogg a reformer? Was she a reformer who became a non-reformer? Is she a reformer but just not as reformy as reform has moved? Was she never a reformer? I’ll get to this at some point, but this is why it can be hard to talk about “reformers,” because no one can agree on who counts as a reformer in the first place. I’ve often viewed Brooklyn’s Eric Gonzalez as one of the more successful, ambitious (but low-key) reformers out there, and I’ve had people tell me that he isn’t one at all. ↩︎

- I use “white” here, and throughout, to refer to those who identify as non-Hispanic white. It can be awkward to keep stating that, though, especially when referring to the negative: “majority-non-non-Hispanic-white” is a logic puzzle, not a demographic description. ↩︎