Election Day was a bad day for criminal legal reform. Not just because Trump’s victory means that the Heritage Institute will try to harass if not oust reform prosecutors it dislikes, but because in many cases reform prosecutors lost directly in local elections (although there was a solid win or two). And they likely lost because the political vibes of this election were “crime is out of control” … even though we are currently in the middle of a historic drop in the homicide rate. I mean, Philadelphia–home to the most high-profile reform prosecutor in office–is on track to have the lowest number of homicides since 2014, and the third lowest in almost two decades.

The vibes are thus untethered from reality, at least from the narrow reality of crime itself.1 The challenge, of course, is that simple fact-checking cannot shift vibes, at least if aimed at the public. But those vibes do not just emerge out of nowhere–for large swathes of the public, they are very clearly driven by the stories the media tells and what narratives the media chooses to emphasize (or, arguably, just create).2 So that is my audience here, and why I think insisting that the facts are what the facts are still matters. The facts can shape the stories that the media chooses to tell and how they tell them, the context in which they situate their narratives, how the assignment desks pick their issues, etc., etc., etc.

Vibes do not change on a dime, but vibes will not change for sure if people adopt a “facts don’t matter” nihilism. And that nihilism is likely simply wrong on the facts.3 It’s true that asserting facts is not a fast fix, and it likely will often appear futile, but if the past fews years have taught us anything, it’s that long-run messaging efforts can yield huge dividends, even with many short-run setbacks.

So here I want to summarize what the “facts are” when it comes to reform prosecutors, focusing on two big issues: their impact on crime, and their impact on racial disparities.

There is going to be a fair amount here, so I’ll provide a short tl;dr here for each chunk. Click on the link in the overview, and it’ll take you to a more extensive discussion of the research out there, along with links to all the papers (ideally ungated when possible).

And two caveats:

First, my project at this point is to provide an overview of the literature, not a formal meta-analysis or systematic review of the literature. I’m personally a strong proponent of such reviews, and perhaps one will emerge from this, but at this point that’s a much more distant project. But the risk with more-informal overviews, of course, is that sometimes more-formal approaches yield insights that simple result-counting, here’s-the-consensus view can’t detect.

And second, this is very much a work in progress. If there are any papers you think I missed here, please send them to me. And I would like to keep this page updated, if only for myself, but also for anyone else in need of the numbers. So please keep sending new stuff to me too, if you think I’ve missed it. Thank you!

The Basic Points

- To start, who even is a “reform” or “progressive” prosecutor?4 There have been a few efforts to pin this down, but it will always remain a rather blurry term–and, of course, the outcome of any test of how reform prosecutors affect crime vs. traditional prosecutors may turn in part on who is slotted into which group. The relevant papers are here.

When it comes to the most important political question–the impact of reform prosecutors on crime–it may make sense to break the studies up into two categories: macro and micro. The macro studies look at how the election of a reformer seems to impact county-level crime rates, while the micro studies take advantage of person-level data to ask how individual outcomes differ by the type of prosecutor (or prosecution) they face.

- The macro studies consistently find no evidence that electing a reform prosecutor leads to more violent crime (although studies are not always looking at the same violent offenses). One study finds a non-trivial increase in property crimes (of about 7%), but most other studies seem to find little to no impact on property crimes either. Papers are here.

- The micro studies indicate that less aggressive responses tend to lead to lower rates of recidivism, and this happens both in studies that limit themselves to lower-level misdemeanors and those that include more-serious felonies. One paper has an intriguing result about the risks of non-incarceration, which may in some cases increase the risk of reoffending (due to the stigma of a record without the confinement of prison). It is worth noting, though, that there are very few micro studies out there yet. Papers are here.

Public safety is not the only goal of reform prosecutors, however. They are also committed to making the system less racially biased; it could be that the policies which reduce disparities also increase crime (though the above policies suggest any such effect is small at most), forcing reformers to balance competing goals.

- Studies do suggest that the election of a reform prosecutor reduces racial disparities, although they also suggest that strong disparities still persist. A throughline I can see emerging from these papers is that some reform policies actually exacerbate the relative rate of punishment because they decrease the absolute rate of punishment for everyone (so any given white or Black person’s risk of punishment declines), but do so more for white people than for non-white ones. The normative implications of this can be tricky. Papers are here.

Finally, it’s worth asking if maybe one reason reformers don’t have a big effect on (at least) violence is because they aren’t able to accomplish all they want: in other words, is the takeaway that reforms don’t matter or reforms don’t happen, either because of resistance within the reformer’s office, or from actors outside the office (police, judges).

- Some studies do suggest that the impact of an election of a reformer on case outcomes can be less than reform’s advocates might think or expect. But some of these results are likely due to short-term adjustment effects of having a new head prosecutor (as at least one study explicitly notes), and in at least one other case the resistance (by police) was enabled by a weak reform policy. Papers are here.

Finally, I want to note that I will not talk much about bail reform–either formally via legislative changes, or informally via bail requests by line prosecutors–here. It’ll be my next post for sure, but this post is going to be long enough, and it deserves a post of its own regardless, since it operates in its own, if adjacent, political sphere. Ditto most data on diversion, which is a popular policy of reformers, but again, one that requires its own separate discussion.

Who Is a Reform Prosecutor?

Classifying reform prosecutors is not easy. It can be hard to identify who counts just based off of the rhetoric (some reformers in more conservative districts try to keep their reform-ness quiet, while some traditional candidates in more progressive counties talk the talk of a walk they won’t walk); with our current data, going further and trying to classify them by actual conduct is, in all but a few places, all but impossible.

That said, there have been at least four efforts to date to try to do so. All are useful, none is at all definitive, although I’d imagine that the overlap is fairly high across them.5 One (mine) relies on no formal rules, another (Agan et al.) relies on an association’s membership list, and two others (Hogan and Mitchell et al.) attempt to develop more-transparent checklists and scorecards, albeit checklists and scorecards that rely on inescapably arbitrary cutoffs and scores–since what counts as “progressive” is a political concept, not a quantifiable one.

- Pfaff, Reform Prosecutors, Fordham Urban Law Journal (2023) (published here, will eventually be updated here):

- How Classified: I relied on the Agan et al. list discussed below, discussions of elections from Bolts.com, and my own personal perspectives, with each source indicated in the list. The one thing that sets my list apart from all others is that I not only track candidates who won, but also those who lost. It is impossible to assess the politics of reform without looking at the losers alongside the winner. Otherwise you run into the very bad, very under-appreciated problem of selecting on the dependent variable.

- Agan, Doleac, and Harvey, Prosecutorial Reform and Local Crime Rates, Working Paper (2022) (SSRN link here)

- How Classified: They received a list of 65 reform prosecutors from an unnamed association that works with reform prosecutors. How that association made its decisions is unclear.

- Hogan, De-prosecution and Death: A Synthetic Control Analysis of the Impact of De-Prosecution on Homicides, Criminology & Public Policy (2022) (paper is here, no unwalled version I can find)

- How Classified: Hogan provides a list of 15 factors that make a reformer a reformer, and counts as a “progressive” anyone who satisfies 10 or more of the 15. He then provides a list of 13 factors for a “traditional” prosecutor, and counts as traditional anyone who satisfies 9 or more of the 13. All other prosecutors are “middle.” He claimes his list tracks that in Agan et al. fairly closely.

- A Note on Hogan: Hogan uses a synthetic control model to argue that Krasner’s election led to a sharp increase in homicides. His paper faced serious immediate criticism, and Hogan declined to share his data in response. The primary repudiation of Hogan’s paper is this by Kaplan, Naddeo, and Scott; see also this detailed analysis of both Hogan and Kaplan et al., which comes out strongly against Hogan’s claims. As a result, I don’t discuss Hogan in more detail below, but I do want to acknowledge the paper’s existence and its results here.

- Petersen, Mitchell, and Yan, Do Progressive Prosecutors Increase Crime? A Quasi-Experimental Analysis of Crime Rates in the 100 Largest Counties, 2000–2020, Criminology and Public Policy (2024) (official link here, ungated here):

- How Classified: Focusing just on the 100 largest counties, they develop a nine-category list with 29 subcategories, with each subcategory scored on a 1/0 basis. If a prosecutor scored 1 in any one subcategory, they were classified as “satisfying” that category, and “progressive” prosecutors were those who scored at least a six out of nine.

Macro Studies

As noted above, the papers listed here consistently find no impact of electing a reform prosecutor on violent crime, and only one finds any real impact on property crime. In short, the facile claim that reform prosecutors are a major engine of lawlessness is simply lacks empirical support.

- Petersen, Mitchell, and Yan, Do Progressive Prosecutors Increase Crime? A Quasi-Experimental Analysis of Crime Rates in the 100 Largest Counties, 2000–2020, Criminology and Public Policy (2024) (official link here, ungated here):

- Key Finding: reform prosecutors have no impact on violent crime, appear to increase property crime by ~7%, with the effect stronger in the second half of their data.

- Prosecutor Classifications: This paper classifies prosecutors as reform or traditional based on the approach discussed above, looking at the largest 100 counties.

- Crimes: UCR index crimes (so felonies). One concern here is that they look at data at the county level, not city–and while it’s true that the county is the correct level for assessing what prosecutors do overall, (1) it’s quite possible their impact may differ between the city and its suburbs, and (2) county level UCR data is even more difficult to use than city-level, and the authors don’t explain how they controlled for the (relative) mess that is non-urban UCR data.

- Methodology: Difference-in-difference regressions.

- Agan, Doleac, and Harvey, Prosecutorial Reform and Local Crime Rates, Working Paper (2022) (SSRN link here):

- Key Findings: No apparent post-election change in levels of the crimes in 35 counties that elected reform prosecutors (although results vary a bit across some robustness checks, but not significantly).

- Prosecutor Classifications: They received a list of 65 reform prosecutors from an undisclosed association that works with reformers (I have a guess, but no inside info). Of these 65, 35 provided usable data.

- Crimes: They look at homicide, assault (unclear if simple and aggravated or just aggravated), robbery, burglary, theft, vandalism, and drug crimes. They don’t state why they chose these specific crimes, which is unfortunate, since the list both excludes crimes that part of the core UCR index offense group (like rape), and include crimes like vandalism and drugs that are not. It could have been an effort to look all degrees of severity, and there’s nothing sacrosanct about the UCR Index crimes. But I’d like to know why these specific ones.

- Methodology: Difference-in-difference regressions.

- Foglesong, Levi, Henry, Bouchot, and Wildeman, Between Violent Crime and Progressive Prosecution in the United States, Working Paper (2024) (link here):

- Key Findings: Looking at a wide range of measures of both violent and property crime across “hundreds” of cities and counties, it finds no evidence of a link between reform prosecutors and homicide, and noisier but similar results for shoplifting as well (an effort to see if there is a link between reformers and the surely-overstated retail-theft sprees).

- Prosecutor Classifications: The report relies on Hogan’s classification, discussed above.

- Crimes: The homicide data comes from the Major City Chiefs Association data for cities, and then CDC data for non-urban parts of the counties (given the challenges posed by non-urban crime data).

- Methodology: Graphical comparisons of trends.

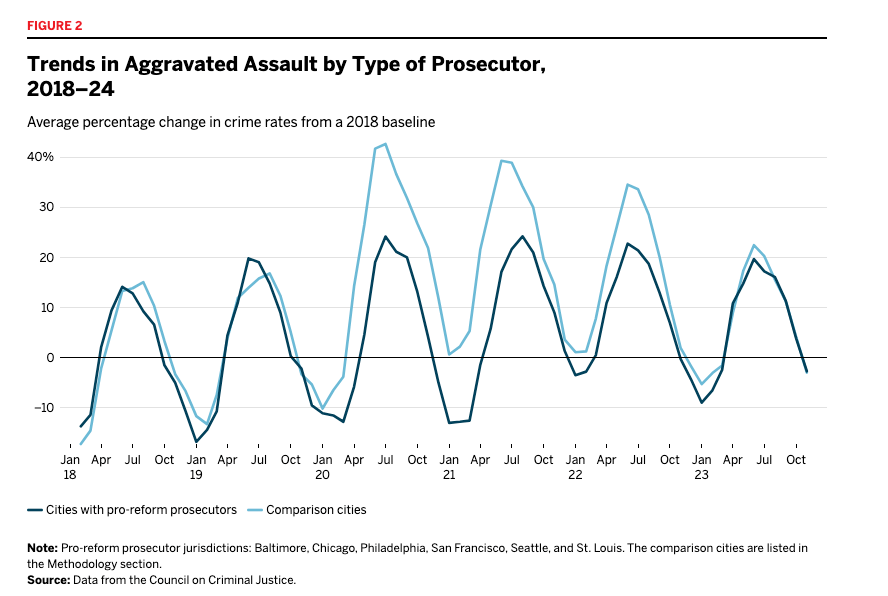

- Eisen, Kang, Grawert, and Seid (Brennan Center), Myths and Realities: Prosecutors and Criminal Justice Reform, policy brief (2024) (paper here):

- Key Findings: Using graphs, they find no comparable difference in crime trends from 2018-2024 across several cities and several crimes.

- Prosecutor Classifications: The reform cities (and it appears to be cities, not counties, even though several of these cities are part of broader counties) they chose are Baltimore, Chicago, Denver, Philadelphia, Seattle, and St. Louis, as well as (in other analyses) Los Angeles, Boston, and Austin. They drew on the three major classifications above (Agan et al., Hogan, and Petersen et al.).

- Crimes: Homicide, aggravated assault, and larceny. Like with other papers, it is unclear why these crimes were chosen over others, and how generalizable the results are. Aggravated assault and larceny, however, are the most numerous violent and property crimes, respectively, and homicide the most serious of all crimes, so there is some logic to the choice. But that does not solve the external-validity issue.

- Methodology: Graphical comparisons of trends in crimes in the reform cities (sometimes separated out, sometimes in aggregate) vs. a collection of 24 “control” cities (although not all cities are used as controls in all analyses, and the published study does not explain why the 24 specific cities were chosen (some of which, like Chandler, AZ, are not immediately obvious choices)).6

- Arora, Too Tough on Crime? The Impact of Prosecutor Politics on Incarceration, working paper (2018) (paper here):

- Key Finding: Republican prosecutors impose tougher sentences than Democratic or Independent prosecutors, but the paper does not find any statistically significant7 evidence that these longer sentences reduce crime at the county level (point estimates show declines in rape and aggravated assault, increases in murder and rape, but all numerically small).

- Prosecutor Classifications: This is paper written before reform prosecution had really taken off, and instead looks at ideological differences: Republican vs. non-Republican candidates in 1,400 competitive (general) elections between 1981-2014. The logic carries over to reform vs. non-reform prosecutors–although it is worth noting that in many large counties the challenger will likely run in the primary, not the general, so there is a potential external-validity issue here.

- Crimes: Aggregate UCR Violent and Property (i.e., Index) crimes.

- Methodology: Regression discontinuity, built around the switch in outcome at 0.5 of the vote share.

Micro Studies

- Agan, Doleac, and Harvery, Misdemeanor Prosecution, Quarterly Journal of Economics (2023) (final paper here, ungated working paper here):

- Key Findings: The decision by an ADA not to prosecute a misdemeanor charge leads to sizable reductions in new criminal complaints (-60% over one year, -53% over two). The effect is even stronger for defendants with no prior record (-80%!), suggesting that that first record is a significant source of future risk. As the paper notes, there’s already a literature showing how misdemeanor convictions jam up things like employment–so the results here suggest that non-prosecution not only reduces the risk of rearrest, but avoids harms to employment, etc.

- Prosecutor Classifications: The data here are entirely from Suffolk County (Boston), MA. The data range (2000-2020), however, includes mostly time when Boston did not have a reform prosecutor (Rollins assumed office in January 2019).

- Crimes: Misdemeanors, but they then exclude any cases where there was any sort of felony charge, or any misdemeanor involving violence or guns, since those would likely trigger more supervisory oversight and undo randomization (discussed next). Their sample comes to ~67,000 cases over 20 years. This could limit the generalizability of their results, however, if we think those charged with guns or violence pose qualitatively different risks–although other studies discussed here suggest that may not be a serious concern.

- Methodology: As-random assignment to behaviorally different ADAs. Non-violent misdemeanor cases in Suffolk are randomly assigned to ADAs, and those ADAs differ in their proclivity to file charges. This effectively creates something akin to a randomized trial, as long as the assignments and behavior are really random (thus the exclusion of cases that trigger more oversight). It is worth noting that the authors only have ADA identifiers for 33% of the cases; they assess the impact of the omitted cases, and find that it seems unlikely it’d alter their results in any meaningful way.

- Owusu, Presumptive Declination and Diversion in Suffolk, County, MA, working paper (2022) (paper here):

- Key Findings: Under Rollins, prosecution for non-violent misdemeanors fell by ~10%, and those on her official decline-to-prosecute (DTP) list by ~5%. The papers finds very small (1% or less) and statistically insignificant declines in prosecutions of felonies. The paper also finds equally small (~1%) but statistically insignificant decline in recidivism (measured by new arraignments) among those facing non-violent misdemeanor prosecution.

- Prosecutor Classifications: The study here focuses just on Suffolk County (Boston), MA. Data is 2015-midyear-2021 (Rollins assumed office in Jan. 2019, and was still there in midyear-2021), focusing on the impact of Rollins taking office on pre-Rollins trends.

- Crimes: All non-violent misdemeanors, with a special focus on the subset that were on the DTP list. Like with the Agan study, the exclusion of violent offenses (excluded because they were not the subject of reform efforts) suggests caution with extrapolating these results to more-serious cases (it may be fair to! but studies that exclude violence are not the ones that show that).

- Methodology: Event study for the impact on decisions to prosecute, difference-in-difference for the impact on one-year recidivism.8

- Goldrosen, Null Effects of a Progressive Prosecution Policy on Marijuana Enforcement, Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law and Society (2022) (paper here):

- Key Findings: Ken Thompson’s policy to refuse to prosecutor marijuana possession crimes did not produce any significant decline in marijuana arrests.

- Prosecutor Classifications: Just focusing on Ken Thompson, who the elected District Attorney for Kings County (Brooklyn), NY, from January 14 until his death in 2016.

- Crimes: Low-level marijuana charges.

- Methodology: Difference-in-difference, with other NYC boroughs as the control groups. Two points to note, one made in the paper, the other not. First, as the paper acknowledges ,Brooklyn differed from other boroughs even before the treatment (less aggressive towards marijuana arrests), which can pose problems for DinD estimates. Second, a point not raised in the paper, my understanding is that Thompson’s policy contained a loophole that can’t be seen in the data: his non-prosecute policy, IIRC, applied only in cases where the marijuana was concealed (like in a pocket) at the time of arrest, but not where it was publicly visible or being smoked. I had one public defender complain to me once that right after Thompson’s policy, all his clients suddenly started carrying their weed publicly … at least according to police reports. Unfortunately for the identification strategy here, the statutory offense is the same in both cases. So it is impossible to see if Thompson’s policy had no effect, or if it pushed the police to change tactics in response to a loophole that is invisible in the data.

- Amaral, Loeffler, and Ridgeway, Prosecutorial Discretion Not to Invoke the Criminal Process and Its Impact on Firearm Cases, Journal of Criminal Justice (2024) (paper here, no unwalled version):

- Key Findings: Krasner’s decision in Philadelphia to shift away from minor cases did not seem to increase the resources available to go after gun cases (which were always a priority for the DA’s office), although the authors note that a short-term decline in seasoned attorneys could have played a role in undermining any resource reallocation. They also find that rate of rearrest, including for violent crimes and gun offenses, appears to fall for those with dismissed gun charges in the Krasner era vs. the years that came before (odd-ratio of ~0.9 for violence, ~0.7 for guns).

- Prosecutor Classifications: Just Philadelphia, so focusing just on Larry Krasner, a clear reformer.

- Crimes: For caseloads, looks just at gun offenses, but for recidivism it examines all offenses (committed by those initially arrested for gun offenses).

- Methodology: Cox hazard model (for time-to-adjudication analysis), logistic regressions for most other analyses.

- Ouss and Stevenson, Does Cash Bail Deter Misconduct?, Am Econ J: Applied Econ (2023) (paper here, unwalled working paper version here):

- Key Findings: Using Krasner’s refusal to seek bail in many cases, they estimate the impact of cash bail as a deterrent, and find that eliminating cash bail does not lead to any increase in non-appearance or rearrest. (The study examines the impact of cash in particular, because almost all released without bail under Krasner would have been released with cash bail before: overall release rates don’t change after adoption of the policy, just the conditions of that release.)

- Prosecutor Classifications: Just Philadelphia, so focusing just on Krasner.

- Crimes: Look at offenses just in the 6 months before and after Krasner rolls out the no-cash-bail policy (Feb 2018), using the list of 25 low-level offenses named by Krasner as subject to the policy (but dropping marijuana possession, prostitution, and retail theft–about 10% of the sample–because they were subject to other changes at the same time).

- Methodology: Difference-in-difference.

Impact of Reform Prosecutors on Disparities

- Owusu, Presumptive Declination, cited above.

- Key Findings: Among the DTP cases, the share of defendants who are Black rises slightly, from 40% to 42%, although the absolute number of Black defendants drops by 2% (and by 5% for all non-violent misdemeanors). Black share rises because white declines are even bigger (5% and 7.5%, respectively). This is, I think, a common outcome will appear in a lot of papers to come, and makes it tricky to interpret

- Prosecutor Classifications: Just Boston, as noted above.

- Crimes: Non-violent misdemeanors in general.

- Methodology: Event-study for the impact on prosecutorial decisions.

- Smiegocki, Metzger, and Vinton, The Difference a DA Makes, Ohio St J Crim L (2024) (paper here):

- Key Findings: The election in 2018 in Dallas County, of John Creuzot, a reform prosecutor, led to a sharp decline in marijuana charges. The authors point out that while police referrals for marijuana prosecution fall from 2018 to 2019 by 30%, the share of those who are referred who are Black rises, from 54% to 56%. This, of course, also means that the absolute number of Black people referred for prosecution falls by ~30%. Worse ratio, better absolute outcome.9 This parallels the results in Owusu.

- Prosecutor Classifications: Just looking at Dallas County, TX, so the only DA here is John Creuzot, widely accepted as a reformer.

- Crimes: Low-level marijuana arrests.

- Methodology: Graphs and summary statistics of case data.

- Mitchell, Mora, Sticco, and Boggess, Are Progressive Chief Prosecutors Effective in Reducing Prison Use and Cumulative Racial/Ethnic Disadvantage? Evidence from Florida, Criminology & Public Policy (2022) (paper here):

- Key Findings: The authors attempt to break down the impact of reform policies on each step of the process (dismissal, diversion, transfer, and then post-guilt (if guilty) treatment. They find that the impact of reformer is statistically insignificant at each stage but has a cumulatively-significant impact on reduced risk of conviction (10 point, or 20% decline), and prison (6 points, or 55%). Looking at racial biases, they find little evidence of bias in traditionally-run jurisdictions until conviction, at which point Black defendants see a greater risk of prison (and thus a reduced gross risk of probation). In reform jurisdictions, Black defendants face higher rates of dismissals, a lower risk of conviction, and a lower risk of jail time, but the same risk of prison conditional on conviction. In traditional districts, white and Latine outcomes are the same, but in reform jurisdictions Latines have a lower risk of conviction.

- Prosecutor Classifications: Using their list (above), and limiting themselves to Florida in 2017, the authors classify Nelson, Ayala, Rundle,10 And Warren as reformers, and the remaining SAs in Florida as traditional prosecutors.

- Crimes: A random sample of all felony cases filed in Florida in 2017.

- Methodology: Logistic regressions.

Impact of Reformers on Case Management

- Goldrosen, Null Effects of a Progressive Prosecution Policy on Marijuana Enforcement, Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law and Society (2022) (paper here):

- Key Findings: Ken Thompson’s policy to refuse to prosecutor marijuana possession crimes did not produce any significant decline in marijuana arrests.

- Prosecutor Classifications: Just focusing on Ken Thompson, who the elected District Attorney for Kings County (Brooklyn), NY, from January 14 until his death in 2016.

- Crimes: Low-level marijuana charges.

- Methodology: Difference-in-difference, with other NYC boroughs as the control groups. Two points to note, one made in the paper, the other not. First, as the paper acknowledges, Brooklyn differed from other boroughs even before the treatment (less aggressive towards marijuana arrests), which can pose problems for DinD estimates. Second, a point not raised in the paper, my understanding is that Thompson’s policy contained a loophole that can’t be seen in the data: his non-prosecute policy, IIRC, applied only in cases where the marijuana was concealed (like in a pocket) at the time of arrest, but not where it was publicly visible or being smoked. I had one public defender complain to me once that right after Thompson’s policy went into effect, all his clients suddenly started carrying their weed publicly … at least according to police reports. Unfortunately for the identification strategy here, the statutory offense is the same in both cases. So it is impossible to see if Thompson’s policy had no effect, or if it pushed the police to change tactics in response to a loophole that is invisible in the data (which in turn would mean that a stronger policy would have a bigger effect on police practices).

- Amaral, Loeffler, and Ridgeway, Prosecutorial Discretion Not to Invoke the Criminal Process and Its Impact on Firearm Cases, Journal of Criminal Justice (2024) (paper here, no unwalled version):

- Key Findings: Krasner’s decision in Philadelphia to shift away from minor cases did not seem to increase the resources available to go after gun cases (which were always a priority for the DA’s office), although the authors note that a short-term decline in seasoned attorneys could have played a role in undermining any resource reallocation. They also find that rate of rearrest, including for violent crimes and gun offenses, appears to fall for those with dismissed gun charges in the Krasner era vs. the years that came before (odd-ratio of ~0.9 for violence, ~0.7 for guns).

- Prosecutor Classifications: Just Philadelphia, so focusing just on Larry Krasner, a clear reformer.

- Crimes: For caseloads, looks just at gun offenses, but for recidivism it examines all offenses (committed by those initially arrested for gun offenses).

- Methodology: Cox hazard model (for time-to-adjudication analysis), logistic regressions for most other analyses

.

.

- The challenge we face is that too many people equate disorder with crime. The unhoused person sleeping on the subway is almost surely not a threat (he just wants to sleep), and thus poses no crime risk, but it is an example of “disorder,” and many people mentally count increasing disorder as increasing crime. And disorder may be rising, but “disorder” is a tough term to define, and even once defined it is a tough concept to quantify. ↩︎

- Seriously, look at the “media mismatch” about halfway down that Bloomberg article in the link. It is an absolutely damning indictment of how the media covered crime in NYC: stories of shootings soared at a time of flat or declining gun violence, because it was a political narrative pushed by those who wanted to fearmonger over crime. ↩︎

- Also, constitutionally, I’m simply not a nihilist and never will be, and I view that sort of fatalistic cynicism, especially when wrapped in world-wearied “let’s be real here”-ism, with full James Harden side-eye. ↩︎

- Most people use the term “progressive.” I use the term “reform” because the term “progressive” codes white, and the political base for these prosecutors are non-white communities, especially Black communities. ↩︎

- I obviously need to check that, and at some point in the near future will. ↩︎

- I suppose, if I were being honest, including Buffalo is equally non-obvious, but as a lifelong #BillsMafia member, it makes perfect sense to me. ↩︎

- Too often, academics equate “not statistically significant” with “as a policy matter, we should treat it as zero.” I think this is wrong for a lot of reasons, but that’s a whole separate series of blog posts (in short: we should all be Bayesians, and no one uses the frequentist tools correctly anyway, but like I said, no further comments on this part). But it’s still fair(ish) to read “not statistically significant” as “really noisy, and too close to zero to say with much confidence what is going on.” (Sorta. Like, if the confidence interval for X is [-.0001, 50] and that for Y is [-100,100], should we really say that we should act as if X and Y are equally indistinguishable from zero? (And yes, I know this is sort of a misuse of confidence intervals, but the rough point stands.)) ↩︎

- It is always important to note the window used when measuring recidivism: a paper using a one-year window will produce lower rates than one using a ten-year window if only because of the window size. ↩︎

- Not only does the paper center just the increase in disparities (which is small enough that it could more like statistical noise), but it does not appear to note that this small increase in relative risk implies a substantial decline in absolute risk (unless I missed it, which is possible: but it is still not a major point they emphasize, despite the fact that I imagine that absolute decline mattered a lot for Black people in Dallas). ↩︎

- This one sort of surprised me, and they admit that she was the hardest to classify. In general, classifying the borderline cases is going to be tough for this issue. ↩︎

Great blog. One note, change heritage institute to foundation.

LikeLike