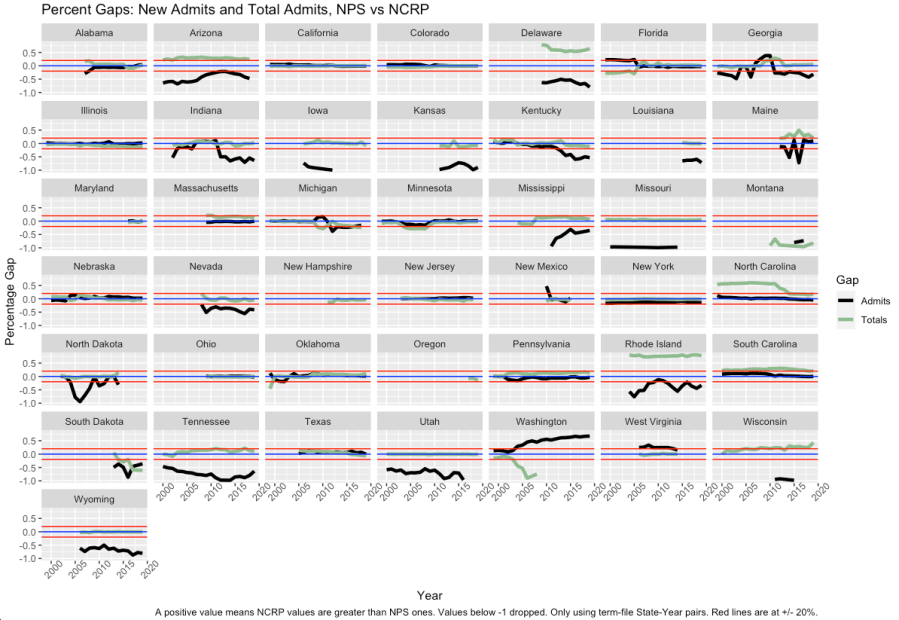

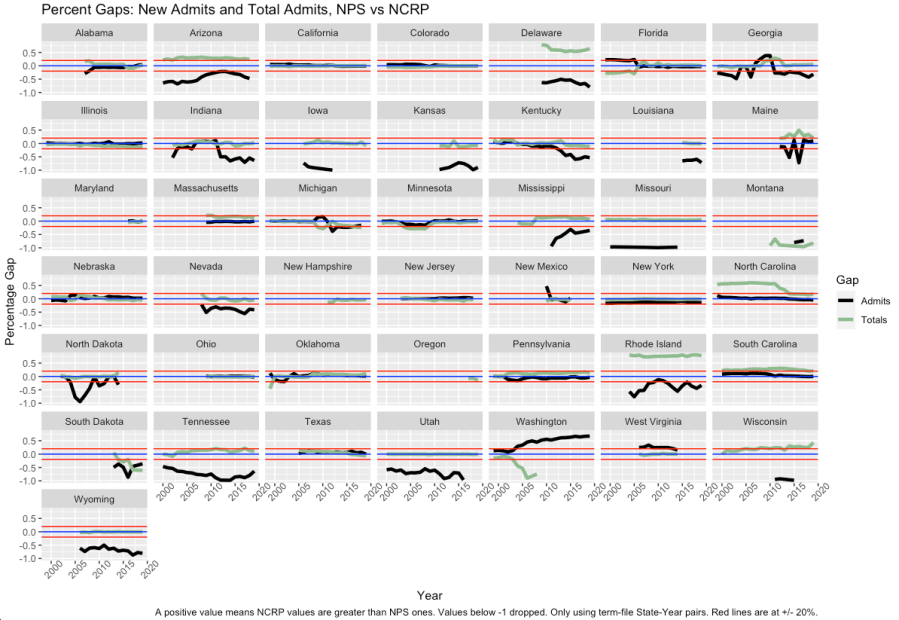

A brief post on conflicts between the NCRP and NPS over prison admissions--a challenge for those doing empirical work on prisons, and a broader warning about the pitfalls in our criminal legal data.

A brief post on conflicts between the NCRP and NPS over prison admissions--a challenge for those doing empirical work on prisons, and a broader warning about the pitfalls in our criminal legal data.

While state-level data suggests that red and blue states alike saw prisons declines, county-level numbers indicate that this seeming bipartisanship is deceptive. Even in the red states, the declines are driven by the blue counties.

With the availability of granular prison data for 2020, it has become clear that the population *most* at risk to suffer bad reactions to Covid--the elderly--was the one to *least* experience early release. In fact, in many states, the number of people over 65 in prison rose over 2020.

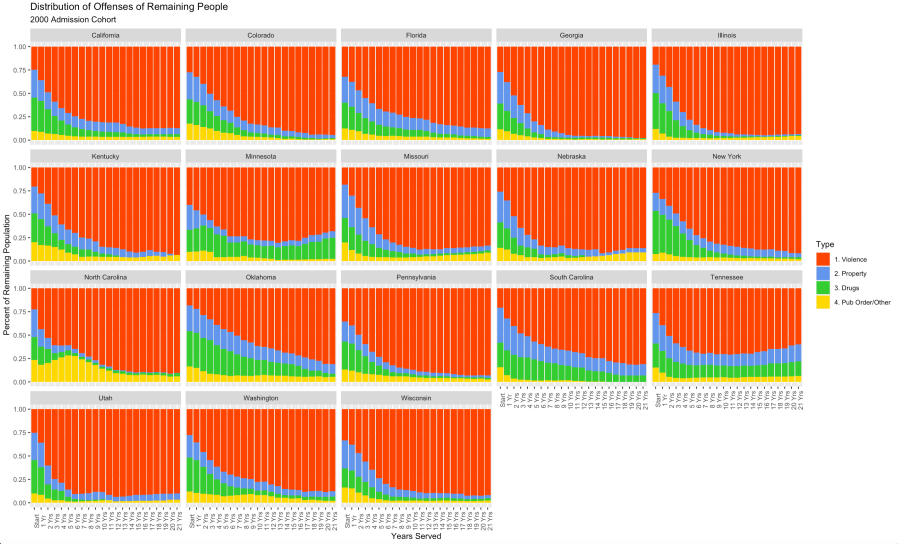

The final look (at least for now) of long sentences: what are those who have been in prison for decades but not yet released serving time for? And the answer, as before, is "a crime of violence."

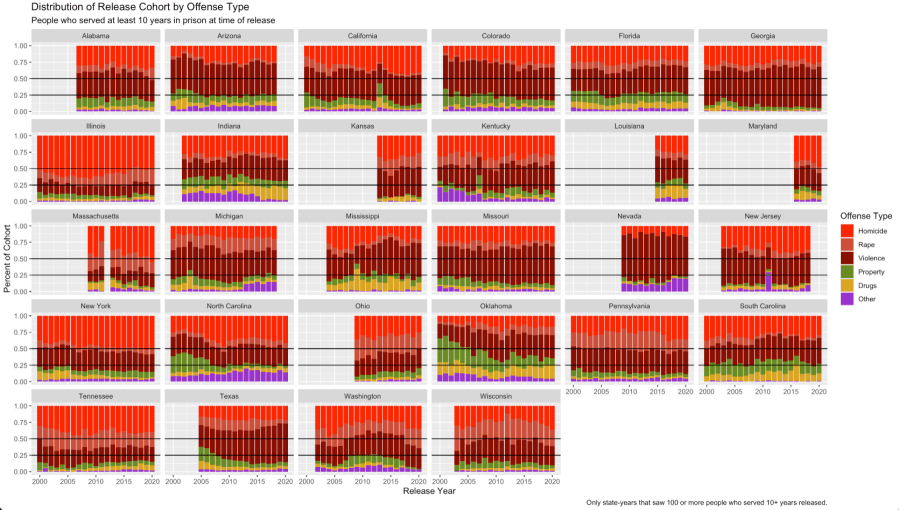

As part of my on-going look at what people are serving time in prison for, I look here at what crimes those who are released after decades in prison had been convicted of. It is, again, a story about violence.

While it is true that criminal sentences in the US can often be longer than those in Europe, the numbers here show both that typical sentences, even for violence, are not that long, and that the long tail of punishment is driven primarily by violent crimes.

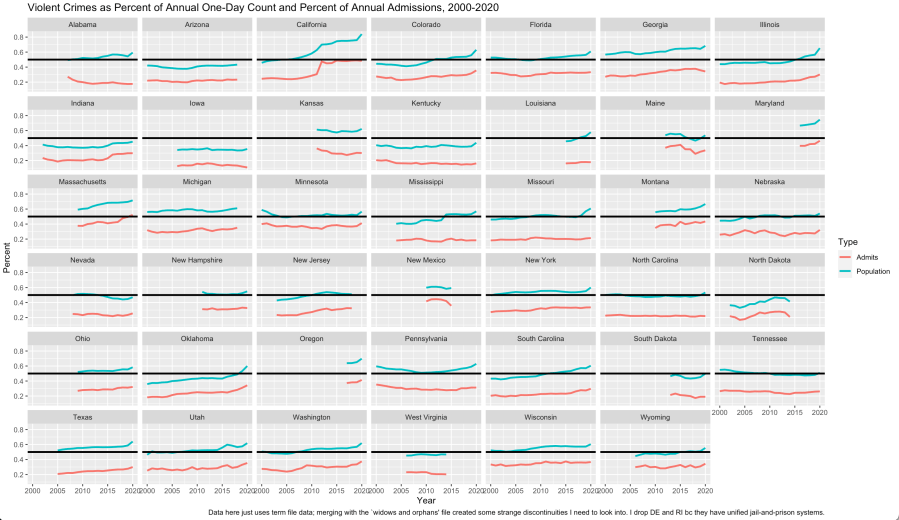

Most of our discussions of prison populations focus on the one-day count of people in prison. Looking at the types of people we admit can tell a different story, and an important one.

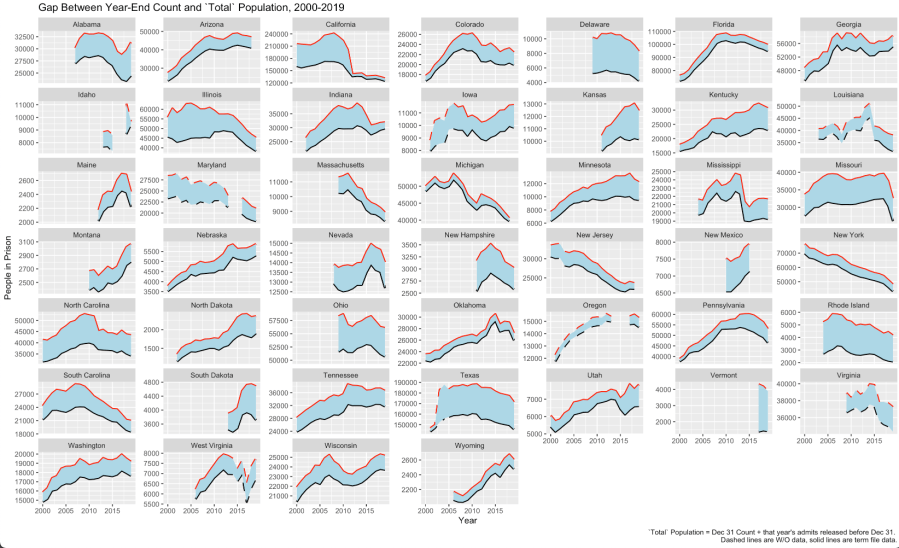

The not-unreasonable way we define our incarceration rate actually misses hundreds of thousands of people each year who pass through our prisons, which means we've undercounted the impact of prisons by millions over the years.